How does one hold power? Can power be shared? How is it perceived and handled?

The participants of the program have dealt with power-under and seen power-over. I wondered about their experience of their own power and sharing the power-with. An illustration of this concept can be found here.

In the context of lending and receiving money, a lender is placed in a position of power over the receiver, who is dependent on them. As more money is equated to increased power in society, this causes an unbalanced power dynamic. It makes one wonder where this comes from. It has a direct connection to the dynamics around fundraising. Fundraising is central to any social entrepreneurship project, and our participants, grassroots leaders in rural India who are addressing the root causes of gender-based violence, also view it as crucial for their growth and impact.

During the session on fundraising, I heard concerns like “We are small people,” “It is difficult for us because we are too small,” “How do we write proposals,” etc.

Then there are other beliefs around money – if you receive it, you have to return it, keep your costs low, asking for it is inappropriate etc. So the funder becomes more powerful.

Where does this idea come from, and how did money get this much power in the first place?

Workshop 1 of Parity Lab’s Acceleration Program introduced me to this group of changemakers. Their stories were diverse, involving trauma and struggles, social structures, and personal challenges. From my one-on-one sessions and baseline assessments, Mathangi and I recognized the need for a larger conversation on power.

Therefore, this workshop was centered on power. We discussed fundraising, and the participants had the opportunity to share stories and engage in meaningful dialogue about power. As we progressed through the workshop, the different shades of power conversations among our cohort became apparent. I am focusing on this theme in this reflection.

Therefore, this workshop was centered on power. We discussed fundraising, and the participants had the opportunity to share stories and engage in meaningful dialogue about power. As we progressed through the workshop, the different shades of power conversations among our cohort became apparent. I am focusing on this theme in this reflection.

All of us have power. It’s like the sun within us and sustains our lives. Yet it gets diminished due to external structures such as patriarchy, gender, caste, class, appearance, skin color, and the internal belief systems created by these external structures. The participants were quick to identify the external structures and slowly recognized these internal belief systems.

Power is not easy to understand.

One participant said in Hindi, “Hum to chote log hain” (we are small people).

This narrative of powerlessness is believed by a woman who underwent a child marriage, had two children very early in life, and yet went on to get an education and set up an NGO that supports other women who are alone. And this is just one story among the 10-12 people who attended this workshop.

This experience caused me to reflect deeply on my own power (or lack thereof).

This experience caused me to reflect deeply on my own power (or lack thereof).

How can I hold my power in a way that serves our cohort and enables them to discover and leverage their own power?

As the workshop proceeded, I watched as the leaders began to claim their power by sharing their own personal experiences. Throughout the course of the workshop, I began to wonder if learning to claim power in this way reflected the concept of power-with.

In our workshop, we created a structure for participants to get to know one another. We hypothesized that one simple way to shift power to the participants would be to encourage curiosity as facilitators. We also opted to approach the session in an unstructured manner to further balance the scales. As one participant mentioned, “The facilitators also become symbols of power. With that power around, asking questions and direct engagement becomes difficult.” As facilitators, we, too, have to balance instructions and explorations.

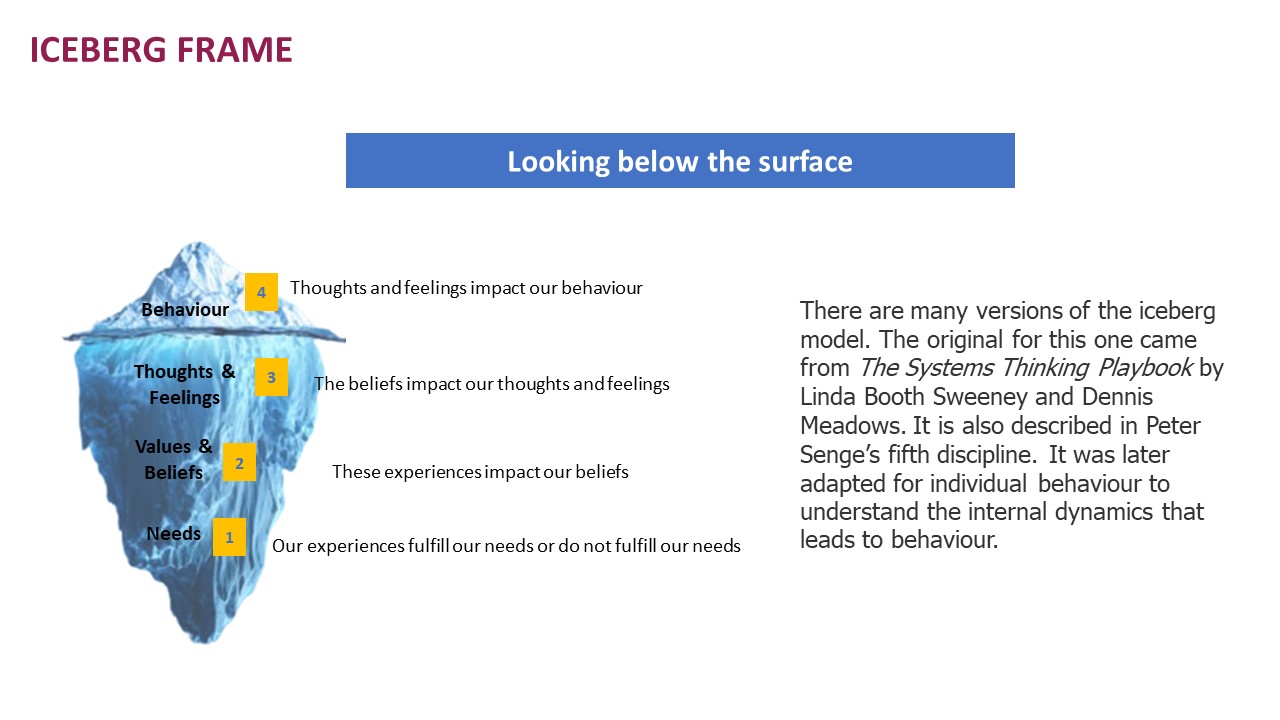

One tool for exploring these responses to structure is the Iceberg Model.

We explored various behaviors – not speaking up, not asking questions, giving so much reverence to age or knowledge that it becomes obedience, or an inability to say no, and so on. External structures influenced by our parents, teachers, mentors, and social and political environment meet some of our needs but often demand behaviors in exchange. Therefore, some of our needs are unmet, which engenders beliefs. These beliefs may create emotions such as fear, anger, disgust, or sadness, thus leading to ineffective behaviors. To overcome this negative cycle, we must begin to question these beliefs, find ways to meet these unmet needs and focus on unpacking these emotions. This is why the embodiment of power is so deeply rooted in mental well-being.

The session on power and implementing the Iceberg Model was not easy and triggered some reflections and reactions. In order to encourage community building among our cohort, we designed a session focused on exploring the dynamics of power within our respective communities. As we implemented the Iceberg Model, we recognized the power of shared experiences and the fostering of safe spaces to promote meaningful dialogue. After unpacking our collective experiences around the concepts of power-over and power-under and developing a deeper awareness of how these concepts play out in our lives on a daily basis, I believe that this workshop sowed the seeds of power-with.

One tool for exploring these responses to structure is the Iceberg Model.

We explored various behaviors – not speaking up, not asking questions, giving so much reverence to age or knowledge that it becomes obedience, or an inability to say no, and so on. External structures influenced by our parents, teachers, mentors, and social and political environment meet some of our needs but often demand behaviors in exchange. Therefore, some of our needs are unmet, which engenders beliefs. These beliefs may create emotions such as fear, anger, disgust, or sadness, thus leading to ineffective behaviors. To overcome this negative cycle, we must begin to question these beliefs, find ways to meet these unmet needs and focus on unpacking these emotions. This is why the embodiment of power is so deeply rooted in mental well-being.

The session on power and implementing the Iceberg Model was not easy and triggered some reflections and reactions. In order to encourage community building among our cohort, we designed a session focused on exploring the dynamics of power within our respective communities. As we implemented the Iceberg Model, we recognized the power of shared experiences and the fostering of safe spaces to promote meaningful dialogue. After unpacking our collective experiences around the concepts of power-over and power-under and developing a deeper awareness of how these concepts play out in our lives on a daily basis, I believe that this workshop sowed the seeds of power-with.

by Dr. Sanjyot Pethe, Wellness Associate at Parity Lab

Comments

Post a Comment